It was a crisp, winter morning and I stood outside Manual High School, traditionally one of Denver’s lowest performing schools. Along with twelve other seminary students on an urban ministry site visit, we listened to our professor. “Manual is one of Denver’s oldest institutions,” he said, pointing to the brick edifice. “It opened in 1896, and was named Manual because it was originally intended as a vocational school to train students for manual labor.”

We quietly shook our heads in disbelief. How could educators have such low expectations for their students? Didn’t the founders believe all students could go to college? So great was our 21st century disdain for manual labor that we naturally connected Manual High School’s low academic performance with its original intent: preparing students for the manual trades.

Americans today devalue manual labor with an almost righteous indignation. We can see it in our economy, in our schools, in our entertainment, and even in the church. And it’s causing all sorts of problems. Let’s take these one by one:

Economy. Consider these statistics. The average age of today’s tradesperson is 56, with an average of 5-15 years until retirement. As skilled laborers retire in masses, America will need an estimated 10 million new skilled tradesmen by 2020 (such as a pipefitters, masons, carpenters, or high-skilled factory workers). But even today, an estimated 600,000 jobs in the skilled trades are unfilled, while 83% of companies report a moderate to serious shortage in skilled laborers. The Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and BusinessWeek have all recognized the huge shortage we have of skilled laborers.

Schools. Across the US, as the need for skilled laborers has increased, the number of classes in “tech ed” – traditionally known as “shop class” – have all but disappeared. For example, in Jefferson County Public School District in Colorado, only three remaining schools have any kind of “tech ed” programs – of a district of over 84,000 students. And in Denver Public Schools, there are only two shop classes remaining – and one of them is currently selling all their equipment to local buyers. As high schools prepare youth to be “knowledge workers,” they unload lathes, table saws, and other “vocational ed” equipment in droves.

The assumption that every student should go to a four your liberal arts college has almost become sacrosanct for urban, suburban and rural students alike. Going to a two-year trade school is seen as a path for “average” to underperforming students. As educator Mike Rose has said in his book The Mind at Work about the cultural image of the tradesmen: “We are given the muscled arm, sleeve rolled tight against biceps, but no thought bright behind the eye, no image that links hands and brain.” Real thinking, our schools have taught us, happens in the office, not the shop. And today have a veritable mountain of student debt – an estimated $1.2 trillion in the US alone – and the lowest labor participation rate since 1978.

Culture. Even in entertainment, we’ve persistently devalued trade schools and community colleges. NBC’s satirical TV show “Community,” portrays American community colleges (which train many skilled tradesmen, among other professions) as the pit of the academic world. The show takes place at Greendale Community College, where “Straight A’s” are “Accessibility, Affordability, Air Conditioning, Awesome New Friends, and A lot of fun.” Perhaps community college is “a lot of fun,” but such merciless mocking finds its way into the future plans of high school students – plans to avoid trade schools and community college at all costs.

Church. In the past 5-10 years, there’s been a renewed interest among protestants in the topic of work. Three years ago Christianity Today launched the This Is Our City project, which profiled evangelicals working in various industries for “the common good” of their city. Tim Keller’s Redeemer Presbyterian Church in New York City has launched a “Center for Faith and Work.” Gabe Lyons’ Q Cities convenes conferences of culturally-minded evangelicals who work in industries like art, media or education. Conferences, books, and seminars on God and work have multiplied, and evangelicals in finance, business, technology, art, science and nonprofits have received renewed attention. But one sector has largely been overlooked: skilled manual labor.

James K.A. Smith, a professor of philosophy at Calvin College, recently wrote, “Do people show up to your ‘faith & work’ events in coveralls? With dirt under their nails? No? Then whose ‘work’ are we talking about?” Though surely not everybody in the modern economy will have “dirt under their nails” after a day’s work, he makes a good point: where are the examples plumbers, landscapers, carpenters, and electricians among this renewed interest in vocation? And more broadly, where are the examples of craftsman and “blue collar” workers who are intentionally living out their vocations in and through their trade? Are executives and professionals the only ones privileged enough to wed meaning with work?

All of this is strange for at least two reasons. First, we all depend on the work of craftsmen every single day. Whether it’s your HVAC repairman, plumber, or electrician, heat, clean water and even light flow as a direct result of their work. The work of the trades is of the utmost importance for nearly every aspect of modern life.

But as a Christian myself, this cultural situation strikes me as even more strange. After all, the Bible is replete with craftsmen – masons, goldsmiths, gem cutters, potters and weavers. The Bible even states that the first person explicitly filled with the Holy Spirit is Bezalel, whom God filled “with wisdom, with understanding, with knowledge and with all kinds of skills—to make artistic designs for work in gold, silver and bronze, to cut and set stones, to work in wood, and to engage in all kinds of crafts,” (Ex. 31:3-5). And, lest we forget, Jesus was a tekton, translated literally as “craftsman” or “one who works with his hands” (Mk. 6:3).

What has gone wrong here? How is it that we came to devalue the craftsman, to the detriment of our economy, schools, churches and culture? To find answers, we need to look to history.

Losing the Craftsman

Such a disdain for the trades was not always so. In the mid-nineteenth century, craftsmen were an integral part of the professional and scientific community. For example, the Mechanics Institutes of Britain had over 200,000 members, which hosted lectures that satisfied the intellectual curiosity of millwrights, metal workers, mechanics and other tradesmen with evening lectures by professors and scientists.

Likewise, in the 1884 book The Wheelwright’s Shop, George Sturt relates his experience of making carriage wheels from lumber. Previously a school teacher with literary ambitions, Sturt was enraptured with the challenges of shaping timber with hand tools: “Knots here, shakes there, rind-galls, waney edges, thicknesses, thinnesses, were for ever affording new chances or forbidding previous solutions, whereby a fresh problem confronted the workman’s ingenuity every few minutes.”

Manual labor was not only integral to scientific discovery, it attracted many of the best minds of its day. In the 18th and 19th century, some of history’s finest scientists – Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), James Watt (1736-1819), Samuel Crompton (1753-1827)– were also craftsmen who built what they designed, and knew no separation between working with the hands and the mind.

Yet the forces of industrialization were changing the skilled trades. Even as early as The Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith marveled at the efficiencies of the factory: “One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head…Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins a day.” The division of labor could produce more pins in a day between ten people than one person alone could produce in a lifetime.

Although the factory had been around for generations, the automation of work took on a new dimension in 1911, when Frederick Winslow Taylor published his Principles of Scientific Management. As Matthew Crawford has pointed out, Taylor’s work focused on gathering the knowledge of craftsmen, organizing it into high efficiency processes, and then re-distributing that work to laborers as small parts of a larger whole. After extensive time and motion studies, Taylor was able to design processes, overseen by management, which allowed employers to cut labor costs by standardizing much manual labor. According to Taylor, “All possible brain work should be removed from the shop and centered in the planning or lay-out department.” Thus the previous harmony of craftsmen and thinker, skilled labor and scientist, began a long process of separation. A “white-collar” labor force of planners and “blue-collar” mass of workers began to emerge.

The positive side of mass manufacturing was unprecedented wealth creation. In 1913, Henry Ford’s assembly line was able to double worker wages and still produce cars more cheaply than his competitors, allowing thousands to afford an upgrade from a carriage to a Model T. Yet the negative side of automation was the monotonous routines for workers, which, according to Ford’s biographer, meant “every time the company wanted to add 100 men to its factory personnel, it was necessary to hire 963.” Skilled craftsmen would simply walk off the line, with a sour taste for work that made them feel like machines themselves.

(Perhaps business philosopher Peter Drucker was right: “Machines work best if they do only one task, if they do it repetitively, and if they do the simplest possible task…[But] the human being…is a very poorly designed machine tool. The human being excels in coordination. He excels in relation perception to action. He works best if the entire human being, muscles, senses and mind, is engaged in the work.”)

At the turn of the 20th century, engaging work seemed like it was being lost in the cogs of industry – and in the mean time, craft knowledge was bowing to mechanical processes.

In the days when Teddy Roosevelt was preaching the virtues of the strenuous life to East Coast elites, many felt education needed to change to ensure the survival of craft knowledge. Only 4 years after Ford’s assembly line, the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917 gave federal funding for manual training. Yet because the bill established separate state boards for vocational education, it had the unintended effect of separating the trades from a liberal arts curriculum. General education would be focused on the liberal arts (college), and vocational education would focus on specific job skills (trade schools).

The advent of shop class began to track all “blue collar” work – whether the high skilled tradesmen or the low skilled assembly line worker – into a single category. Over time, shop class meant children of “white collar” workers could make a bird feeder or toy car in shop class, but they had little remaining skills of the craftsmen, which for centuries had been passed on through a process of apprenticeship.

We feel the lingering effects of this division between “vocational ed” and a liberal arts education today. Most of those who graduate with degrees in film studies, sociology, or even mathematics or physics haven’t the foggiest idea how to actually fix a car engine, build a table, or wire a light fixture.

Yet the greater effect is the enormous economic problem we now have before us – there are literally millions of “dirty jobs,” as Mike Rowe, the former host of the Discovery Channel Show, would call them. But swathes of young people would would never consider a career in plumbing or construction, despite evidence that these jobs both pay well and are here to stay. Computers and technology have certainly changed our labor force (and will continue to change the economy, as a recent article in The Economist convincingly argues), but they will never change the fact that we live in a physical world – and we will always need physical things because we are physical beings. We will always depend fundamentally on the physical goods – whether made or repaired – that are the unique domain of the craftsman.

Signs of Hope

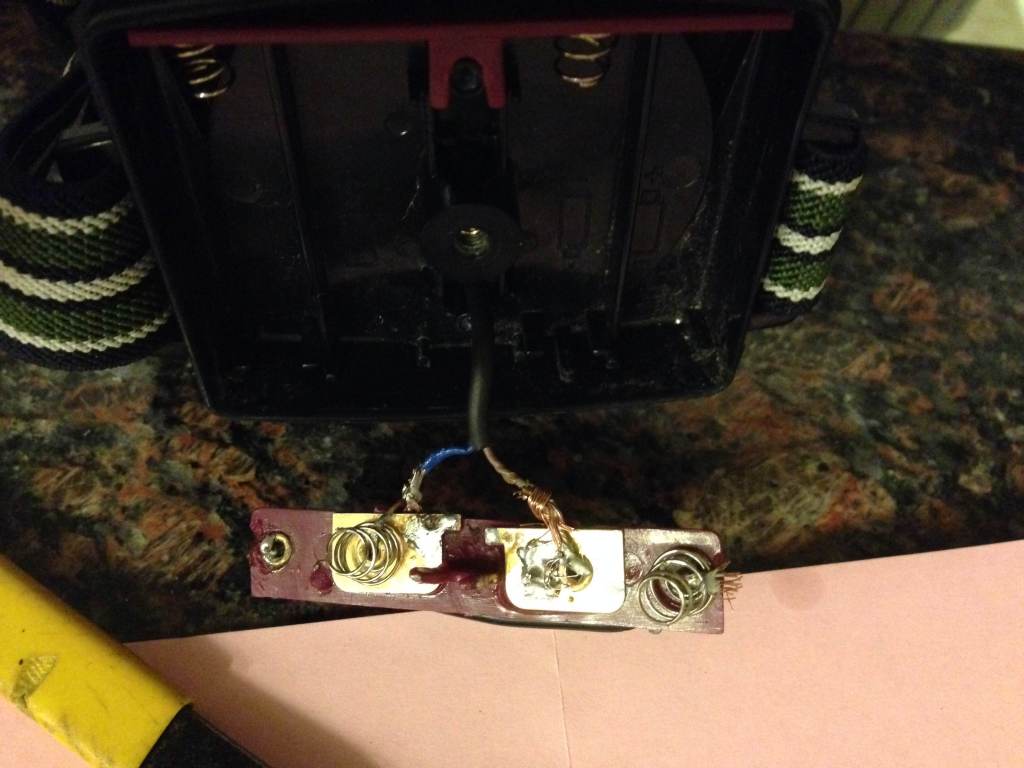

What is to be done about this problem? Although this is a monumental challenge, we can do at least two things. First, praise examples of excellent craftsmanship – from chefs and jewelers to masons and electricians – that arise from above the criticism and display an ethic of skill, beauty and manual intelligence in their work.

For example, every four years, France hosts the Meilleurs Ouvriers de France (MOF) competition. One event features a fierce three-day competition between 16 international pastry chefs jockeying for the blue, white and red striped collar that signifies culinary excellence. Chefs are judged on artistry – the visual appearance of the desserts, buffets and, for example, sugar sculptures – taste – entries have very specific size and ingredient specifications – and work – how clean and efficiently the chefs work; including spotless aprons, no waste (exact planning is required), immaculate kitchens. Chris Hegedus and D.A. Pennebaker, producers of the documentary “Kings of Pastry” said in an interview , “The idea of recognizing excellence in manual trades and elevating them to a status equal to intellectual or academic fields is what is uniquely important about the MOF Competition” (emphasis mine). Indeed, Meilleurs Ouvriers de France, when translated, is “Best Craftsman in France,” a title won only by the finest chefs exhibiting the highest levels of skill and manual intelligence. And France’s competition isn’t just limited to chefs; there are also competitions for stonemasonry, plumbing, tailoring, weaving, cabinetmaking, soldering, glassblowing, diamond-working, and a host of other trades.

In America, Tad Landis Meyers, a photographer, recently published Portraits of the American Craftsman – a stunningly beautiful photo journal of the work of a “lost generation of craftsman.” Scotty Bob Carlson of Silverton, Colorado makes hand-crafted skis; Nell Ann McBroom of Nocona, Texas cuts, dies and sews baseball gloves; Steinway and Sons Pianos in Long Island New York makes pianos “designed to last not just for years, but for generations.” Meyers’ five year journey of photographing American craftsmen has revealed an almost forgotten way of life, defined by careful skill, mastery of the physical world, and satisfying work. Brett Hull of Hull Historical Millwork in Fort Worth Texas says, “The simplicity of the clean lines or the intricacy of the detail are exciting to me. It’s something that just fills my soul.”

But praising excellent craftsmanship can also be more commonplace. Drop a laudatory comment to the construction worker who’s laying pavement; marvel at a gang of conduit that winds itself above light fixtures; choose to buy a table that will last not for years but generations. The simple act of recognition is powerful.

But second, and most importantly, encourage more young people to go to trade school. That’s what more people are doing around Thaddeus Stevens College of Technology in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. They recently announced a $2.5 million dollar grant to expand training programs for high-wage, high-demand manufacturing jobs. And with a a 95 percent job placement rate, minimal student debt, and jobs like an industrial apprentice that can start at $60,000 with full benefits, more students are taking a look at choosing trade school over a 4 year college degree.

I’m not encouraging more young people to be vocational mercenaries (go get the quick money!), but for those students who nod off in British literature (God forbid) but come alive when rebuilding an engine, we must acknowledge that some people are designed to be builders – and that’s okay. It may even get them a better job than their peers who end up as debt ridden, college-educated baristas who can make a mean latte, but find trouble getting into a career.

The craftsman lives on – yet still in the corners culture more enamored with the virtual world than the physical world. But for the sake of our economy, schools, culture and even our churches, we would profit to once again appreciate our culture’s makers and fixers – the craftsmen.

Photo: American Craftsman Project

This essay first appeared in The City, a publication of Houston Baptist University. Also, Chris Horst and myself have a feature essaying coming out in Christianity Today this summer on the topic of craftsmanship and the gospel.

[Exq_ppd_form]

Karla is the Chief Business Development Officer at Weifield Group Electrical Contracting in Denver. In 2014, she

Karla is the Chief Business Development Officer at Weifield Group Electrical Contracting in Denver. In 2014, she