5 Book Recommendations to Rekindle Your Imagination and Impact

When I walk through the door on Friday evening, I can usually feel a slight tingling sensation on my scalp. The speed of the work day – meetings, phone calls, emails, tweets, tasks, problems and exhilarating opportunities – is almost addictive. I can feel my heart rate slightly elevated and my words rushing through my house like a gust of wind. The pain of shutting down my smartphone for Saturday feels like I’m putting down the ring of power.

In the early morning hours, as I sip coffee before my children awake, I wonder who I’m becoming. I find it difficult to carefully listen to those whose lives are vastly different from my own. I find it difficult to consider the pilgrimage of my soul amidst the whir of leadership. I find it difficult to be dazzled by adventure as I was as a child; to laugh and to delight in the tall tales of giants and men; to find the emotional reservoir and depth of character my kids, my wife, and my co-workers need from me.

And I find it difficult to calm myself, and carve out the space, the silence, to read.

For years I’ve loved books. I became a Christian through reading, believing I had discovered a secret the world knew nothing about. But in my 34th year, pressed by responsibility on every side, on the weekends I find it far easier in my exhaustion to turn on the television, justifying that I have nothing left, even to pick up a book. Yet, when I choose the route of easy entertainment, I usually feel drawn out, thin, like “butter spread over too much bread.”

It’s tempting in positions of leadership to read the latest business book, or dilly over the latest news story. Everything is so pressing, so urgent. Yet over the last year, I’ve come to realize what’s most urgent is my own moral formation. It is goodness that my community needs most from me. Literature makes me ask questions about myself, my world, and my work that lean on my heart, and open doors to unforeseen countries of truth.

Here are five books I recommend that have found a home in my imagination, and perhaps can rekindle your own imagination – and leadership – too.

1. The Life You Save May Be Your Own, by Paul Elie

Paul Elie has crafted a stirring biography of four great 20th century Catholic writers: Dorothy Day, activist, bohemian, pacifist, founder of the Catholic Worker, and friend of the poor; Thomas Merton, rebel against the modern world, lover of literature, mystic, and Trappist monk; Flannery O’Connor, novelist of the Christ-haunted south, independent thinker, seer of tension between a longing for the Holy, and an ever-present secular doubt; Walker Percy, physician, melancholy novelist, and Catholic who found stability in faith amidst a family lineage that included generations of suicide.

Percy, O’Connor, Merton, and Day – all great readers before they were writers – became known as the School of the Holy Ghost, each learning about each other’s writings as they struggled to find faith in 20th century America.

The book is hefty, but it reads more like a novel than a biography, carrying readers from one episode to another. The value for leaders today is the book’s theme: “an American pilgrimage.” Each of them was on a spiritual journey, riddled not only with doubt but with illegitimate children, anti-war protests, the the pain of illness. Many of us long for the divine but find faith elusive. Day, O’Connor, Merton, and Percy are friends for the journey of leadership.

For me, spending time with The Life You Save May Be Your Own was not a journey of salvation, but it was certainly a pilgrimage toward sanctification.

2. Island of the World, by Michael O’Brien

Josip Lasta grew up the son of a school teacher in the remote mountains of Croatia. O’Brien’s tale takes the reader through World War II, occupying armies, the suffering and death of innocents, and a one man’s attempt to live a good, human life amidst the dehumanizing engine of the modern world. Island of the World is a story of the courage, pain, and deep introspection of a man – and poet – not famous or wealthy, but whose journey from Europe to America formed him into a full, if bleeding, soul.

Literature, like Island of the World, allows us to feel, to weep, to mourn, and to see in character the moral conviction we long for despite the thousand miniature cuts we incur in life, family, work, and public life.

For O’Brien, the foundation of the world is not found in the city streets, monuments of steel, or, in our day, the cables of broadband laying on the ocean floor. The foundation of the world is love despite pain, hope amidst destruction, a God who suffers alongside side of us.

Leadership can be a lonely journey. After reading Island of the World, I felt a little less alone.

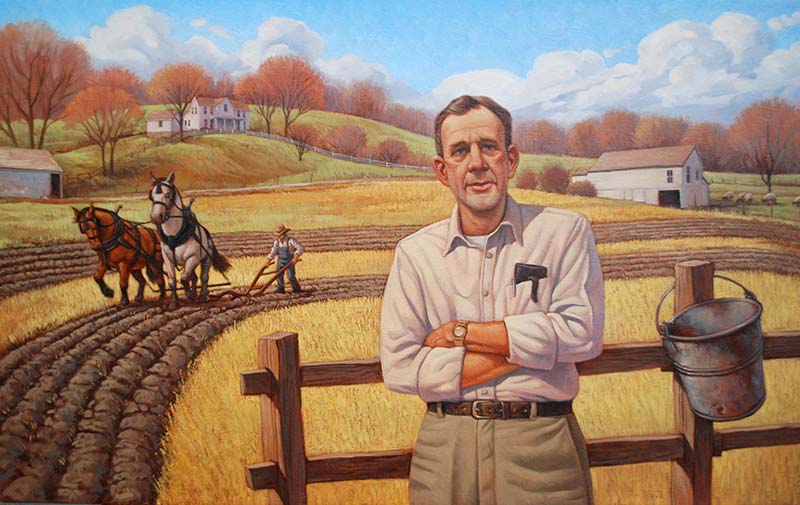

3. Hillbilly Elegy, by J.D. Vance

Vance’s “memoir of a family and culture in crisis” pulls back the veil of America’s working class, which has suffered since the 1970s, especially across Appalachia and the Rust Belt.

Vance’s odyssey sticks in your mind like a splinter: his beloved Mamaw (grandmother) who once taught her drunk husband a lesson by pouring gasoline him and lighting him on fire; his drug addict mother demanding her teenage son to pee in a cup so she could pass a drug test and not lose her job (after Vance refuses, she cries and begs: ‘I promise, I promise I’ll do better. I promise’”); the fierce honor code among hillbillies, demanding each slight be returned tenfold.

After reading Hillbilly Elegy, I felt covered in shame. A confession: I find it easy to look down on poor white people. When taking road trips from Colorado to Minnesota, I stop at gas stations in Nebraska and Iowa and quietly, smugly, look down on poor white people.

But now, after seeing Vance’s childhood, a sheep being raised by wolves (who in turn were also raised by wolves), I felt in my bones the enormous difficulty of cyclical and cultural poverty, and my own smug arrogance for not stopping to see and to know the American poor.

Hillbilly Elegy should be required reading for leaders who often have “hillbillies” working at the bottom of their organizations. This book gives the crisis of America’s working class a human face. And by the end, you come to even love Mamaw – cursing, violent, vulgar and all.

4. To Kill a Mockingbird, by Harper Lee

Much great literature is wasted on bored high school students; it is we adults who need it the most. After re-reading Harper Lee’s perennial classic, I was stunned. Stunned by the ability of a young author in the south to see the “other.”

Atticus Finch – old, scholarly, bright, humble – not only defended Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused of rape, in court, but he could see his inherent dignity despite the swirl of racism in the South. Scout, Atticus’s curious daughter, defuses an angry mob coming to lynch Tom Robinson: “Don’t you remember me, Mr. Cunningham? I’m Jean Louise Finch. You brought us some hickory nuts one time, remember? … I go to school with Walter … he is your boy, ain’t he? Ain’t he, Sir?” It’s as if Harper Lee can see the humanity in even the racist and bigoted. The hero of the story ends up being Boo Radley, the dark recluse thought to have stabbed his father. A strain of compassion and heroism existed even in his heart.

My life leading Denver Institute moves fast. And I love it. But when I move fast, I often put people into simplistic categories: “doesn’t get it,” rich guy, that’s a “get stuff done” person, ignorant, a “nominal” Christian. Harper Lee crushes my categories, and makes me take a second look at each person I meet.

If I have ears to hear and eyes to see, each person is a deep well, filled with virtue and stain, triumph and moral weakness.

5. The BFG, by Roald Dahl

Sheer delight. That’s how I’d describe my experience recently reading The BFG with my 8 year-old daughter.

“Human beans is not really believing in giants, is they?” Well, all of us should, because recovering a sense of wonder is right around the corner. Giants with names like Bloodbottler, Fleshlumpeater, and Childchewer (over 50 feet tall!) drool and gulp humans every night. But the BFG instead eats stinky snozzcumbers, drinks wonderfully delicious frobscottle (which bubbles downward and causes the ever-fun whizzpoppers to lift him into the air), and catches dreams, hearing them whizz through the air with his enormous ears.

Can you remember a time when both a little fear (could giants really be real?) and a sense of adventure (maybe I could be like Sophie and save kids from those terrible beasts!) were just as real as the dinner you ate last night?

Leaders need to laugh, to delight in words like Roald Dahl, and spend more time thinking like children. Children, in the words of children’s author Mo Willems, are not dumb. They’re just short.

Leaders could learn a lot from kids. After all, the kingdom of heaven belongs to them.

This post first appeared on denverinstitute.org. Photo credit.

[Exq_ppd_form]