Jeff Haanen suggests four ways by which a biblical view of retirement (aging) can contribute to a more holistic vision for investing.

Neither the word nor the concept of ‘retirement’ is found in Scripture. Still, the Bible offers much wisdom for growing older wisely and well.

Is the American idea of investing for a retirement of travel and leisure healthy? Does it even satisfy? Or is there a better way?

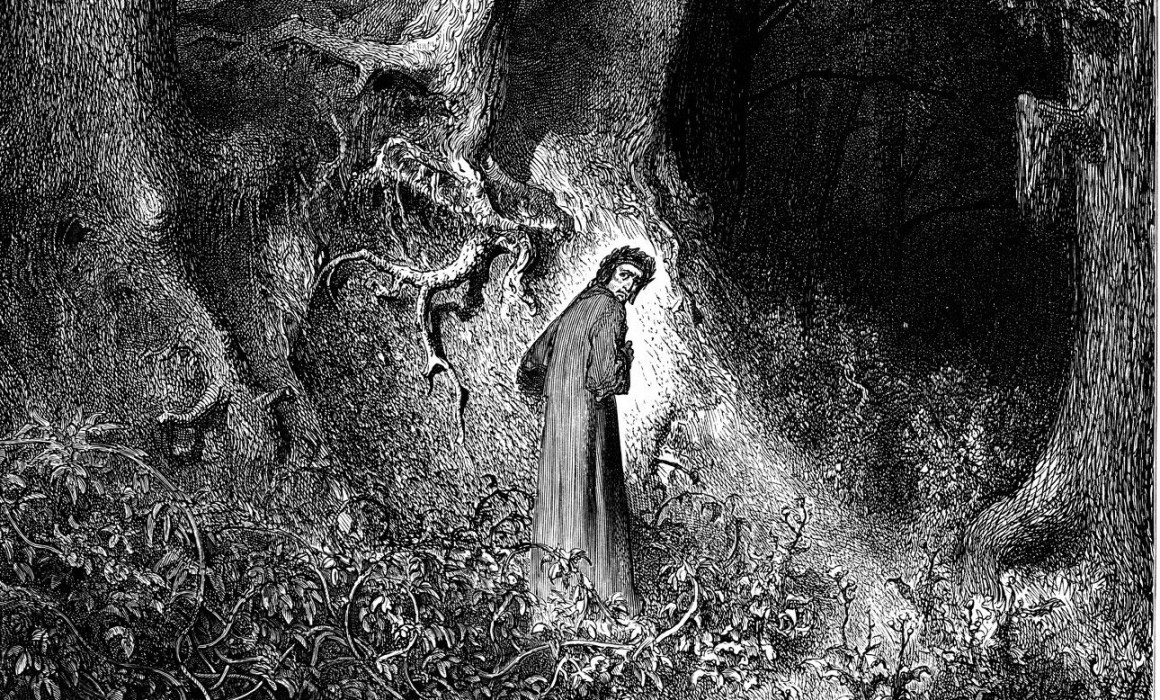

“Midway upon the journey of our life,” writes Dante in the first lines of his Inferno, “I had found myself in the dark wilderness, for I had wandered from the straight and true.”

I wonder if Dante was making a comment on the crafty nature of sin, creeping up from behind like a silent fog when we least expect it…or just the bewildering challenges of being middle-aged.

Several weeks ago, I called Dan, one of my friends, who’s nearly forty. “How are you?” I asked. “Well, nothing new,” he said with sigh. “Same job. Same family. Same house.”

He went on to explain that nothing was wrong, per say, other than feeling the reality set in that he was no longer in his twenties, filled with notions of changing the world. He wasn’t depressed, but aspiration had slowly given way to some combination of responsibility and reality, seeing in one hand a mortgage statement and in the other the scars of a thousand tiny disappointments after almost two decades on the job.

“Midlife, especially for middle-class American men,” wrote Robert Bellah, American sociologist and author of Habits of the Heart, “often marks the end of a dream of a utilitarian self established by ‘becoming one’s own man’ and then ‘settling down’ to progress in a career.” Bellah says that around midlife, many realize that they’ll never be “number one” — senior partner, Nobel laureate, principal, CEO. As these dreams die, finding one’s identity in work dissipates and career trajectories flatten. “For many in middle age, the world of work then dims, and by extension so does the public world at large.”

For years in my own work at DIFW we have seen a trend: young professionals in their twenties and thirties come to our events, press into big social issues, and become Fellows, but participation in our programming drops off in one’s forties and fifties. What’s happening here?

Both my friend Dan and Robert Bellah explain what’s happening. First, in middle age, we must reckon with the crushing loss of professional dreams. You have a job, but the idea that you were going to “change the world” is shown for what it is: a postmodern mirage, built around the slippery, individualistic notion we had believed since we were teenagers: “you can be whatever you want to be.” A cloud of grief, loss, and disillusionment fills our horizon — one we’re quick to push back with entertainment, busyness, or consumerism.

The second reason: golden handcuffs. We reach the midpoint of our careers and we find we’re better paid now than we were in our twenties, but our expenses have grown as well. Mortgage payments, grocery bills, and kid’s activity fees all tamper down our desire to risk building something new, step out on a limb at work, or start a new career. Better to play it safe, even if we feel something inside of us crumbling.

Yet not all submit to the resignation of our hopes in midlife.

I’ve observed that some take an alternative path in midlife that acknowledges our limitations, pursues interior freedom, and embraces failure as the only pathway to growth.

Acknowledge Our Limitations

Gordon Smith, author of Courage and Calling, writes, “To embrace our vocations in midlife means that we accept two distinct but inseparable realities. First, we accept with grace our limitations and move as quickly as we can beyond illusion about who we are. Second, it means, positively, that we accept responsibility for our gifts, and acknowledge with grace what we can do.”

Bishop Ken Untener makes a similar point, very applicable to life at midcareer, “We cannot do everything, and there is a sense of liberation in realizing that. This enables us to do something, and to do it very well.”

Our individualistic society is built around “your success.” And most weeks I see people who mistakenly believe that they can find their life’s purpose in their job. When this illusion dies, they often become disengaged — both from their job and the broader culture. And for those who do make it to the top, often they’ve done so by making work their religion.

But some take a humbler path. They take stock of what they are, and what they’re not. They look squarely at their talents and their limitations. They realize that won’t change culture. But they also realize that they can change the world right around them — co-workers, community, church, and family.

And perhaps even more importantly, they become ok with knowing people who are richer, smarter, better looking, and more talented. Seeking approval for performance is calmed by the steady, lasting approval of God.

Pursue Interior Freedom

When New York Times columnist David Brooks set out to explore his own road to character growth, he realized there are two sets of virtues: résumé virtues and eulogy virtues. Résumé virtues are those you bring to the marketplace and post on LinkedIn — degrees, job accomplishments, accolades. Eulogy virtues are virtues people will talk about at your funeral — humility, kindness, courage.

Our careers tend to compensate and reward us for résumé virtues, but at some point, we realize these goals are thin, and we’ll have to decide whether we’ll make the journey into the interior world.

Rev. Jacques Philippe, author of Interior Freedom,says that if we’re continually looking to the external world for our approval, we’ll never be happy because our circumstances are constantly changing. However, he says we can cultivate deep interior freedom by practicing the virtues of faith, hope and love and by connecting deeply to the source of inner freedom — God himself — which no external power can take away.

Philippe and Brooks both are calling us to making a momentous shift in our lives: from exterior success to interior depth.

In this way of thinking, work becomes not just a way to achieve, but the primary context for our spiritual formation and interior growth. When we’re passed over for a promotion, slighted by a prospective client, or enduring a toxic workplace culture, the question becomes not one of escape to a better job, but instead: who am I becoming?

When the journey toward success in midlife lost its luster, a few decided to take a new, and much more exciting journey, toward whole-heartedness and deep emotional and spiritual health.

Embrace Failure as the Only Pathway to Growth

Winston Churchill once said, “Success is going from failure to failure without loss of determination.” Commenting on this paradox, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks writes, “It is not their victories that make people leaders; it is the way they cope with their defeats — their ability to learn, to recover, and to grow.”

Most people move into middle age with a growing set of disappoints and failures that lead to resignation. “I’ll never get the job.” “I’ll never make a big impact. That was just the naivety of my twenties.”

Yet there are a few who experience the same set of consistent failures and they learn from them. They adopt a growth mindset. They don’t let their ego get in the way and they instead welcome feedback from family, friends, and co-workers. In the process, they ask questions like: What did I learn from that situation? How did I react? And what does this mean for me and for those around me?

The path to leadership is narrow because the majority want to blame others for their problems. The few decide to take ownership over what they can and let the harsh lessons of life refine them like a fire.

Dante had to make the journey first into the inferno before he made his way to purgatory and then ultimately to paradise.

Perhaps the only way out of the dark wilderness of midlife is first to go further in.

Recently I got a prospectus from a faith-motivated advisory firm that outlines what they invest in as Christians. On one level, the responses were predictable. They don’t invest in alcohol, cannabis, pornography, or weapons. And they do invest in companies that have ethical leadership, policies that value employees, and a “positive societal impact.”

But after reading the prospectus, I had to pause and say to myself: this is really, complex stuff.

On one level, investing is quite straightforward: capital should be used to bring about returns. Yet, what is positive societal impact? What companies are “ethical” and which aren’t? Aren’t all companies – like people, a mix of good and bad, moral and immoral? How do you even think through ethics? And which societal impacts are primary, and which are secondary? Why?

I’m not trying to be esoteric. Here’s an example for you for you make an investment decision, shared with me by a dear friend and leader in the faith-based investing space.

Example 1: Building materials company

- The employee stock ownership plan or ESOP is 9.5% of total shares outstanding. To date, 40K employees participate and the company matches up to 6% contribution.

- Their promote-from-within culture focuses on investing in talent and yields a low voluntary turnover rate of 7-8%. Post-college entry-level training program (with average starting salary ~$47k according to Glassdoor) teaches how to manage store P&L. The CEO came up through the same program.

Example 2: Restaurant franchise company

- 95%+ of US franchisees started as drivers or hourly workers in stores. “Everyone is trained to become a manager from the first day”, according to a former franchise employee. Cross-training is the norm.

- Store start-up cost is $300K vs $4-5M for some other large concepts, making franchise ownership accessible to the middle class. According to one industry expert, “for someone making $60K a year, opening a franchise is possible”.

- Franchisees go through franchise management school program to ensure success.

- During COVID, the company paid $10M in year-end bonuses to >10K company employees in addition to bonuses paid in March/April 2020 and expanded/extended sick leave benefits.

Now, both seem to be solid public companies having a good impact on employees and are profitable.

But how do you decide between the two? Returns? Opportunity for low-income employees? Or do you prioritize the product itself: would you rather invest in expanding a building materials company or a fast-food business? Or do you instead decide to look into the environmental practices of their supply chains?

Investment analysis obviously goes through a financial filter. And increasingly so, it goes through some combination of a social or ethical filter. But what of theology? For the secular investment firm, this, of course, makes little sense. (Though, whether they acknowledge it or not, all their investments are going through a philosophical filter.) But for the faith-driven investor, isn’t “the faith once entrusted to the saints” the most central filter for investing in any company (Jude 1:3)?

If so, are you sure that your perspective on faith and investing is coming from historic Christian belief rather than, say, your cultural background, your social class, your family of origin, your education, your political persuasion, or your own church’s emphases?

Let me make that case that every faith-driven investor needs to hire a theologian. Here are three reasons.

1. Combining faith with investing is inherently complex.

Here’s what faith-driven investors are trying to do. They’re trying to take ancient texts written originally in Greek, Aramaic and Hebrew to ancient peoples, grasp the core teachings of these texts enough to then understand the core doctrines of Christian belief developed over 2,000 years of church history, apply those doctrines to the modern social construct of business with all the complexity of finance, marketing, operations, and sales, and then decide on which businesses to invest in based on those beliefs and practices!

To go from the book of Daniel to fintech, or from the Doctrine of the Trinity to human resource practices is not for the faint of heart!

Far too often in the faith-motivated investing space have I seen simplistic interpretations of texts (like the parable of the talents) to investing, without understanding the doctrinal, historical, or social context of particular passages, or even their own biases in reading the Bible as 21st century American Christians. Just like finance, doing theology well requires knowledge, practice, and a breadth of learning.

The reality is, we need experts who can help wade through these waters if we actually want our core investment philosophy to be Christian.

2. Theologians bring a unique set of specialized skills.

Ever since the Protestant Reformation, we’ve believed that since we can all read the Bible for ourselves, we can understand it just as well as the next person. Now, I’m a big fan of everybody reading the Bible, but this has led to a deep devaluing not just of pastors, but those who have literally spent decades studying theology and scripture – like theologians. To say that “anybody can understand the Bible” to a theologian is like me saying to an investor that there’s no difference between a managing partner at Blackrock and an entry-level financial advisor at Thrivent. They’re both equally valuable in the eyes of God, but they’re not both equally competent or knowledgeable when it comes to investing.

Years ago, we at Denver Institute for Faith & Work hired Ryan Tafilowski as a “resident theologian.” He has a Th.M. in ecclesiastical (church) history and a Ph.D. in theology from the University of Edinburgh. He writes and speaks on inter-religious dialogue, historical theology, and ethics. And to top it off, his ability to recall episodes of Arrested Development is astounding (to the great delight of our entire staff team).

Over the years, Ryan has taught our staff team everything from political theology to the doctrine of sin. And when we’re weighing in on tough social issues, ranging from gender to race to immigration to how much profit we should reinvest versus give, his expertise in theological foundations and frameworks has regularly surprised and delighted us. Often, it has completely transformed our views of an issue.

Ryan has education and knowledge that I don’t have. Because this is true, when he speaks, though I’m technically his boss, I’m careful to listen. He actually knows more than I do about the “faith” aspect of “faith and work.” He adds tremendous value to the team, not just in production, but in faithfulness to our own tradition – a tradition I’m still just learning about.

Having a theologian on my staff is incredibly valuable.

3. They’re worth the investment.

Now, the vast majority of theologians don’t know the first difference between public equities and private equity. To that end, they need to listen to professional investors. Yet I believe that professional investors also need to listen to theologians.

I believe it’s worth having a full-time theologian on the staff of every faith-motivated investment firm. They should weigh in on every social, ethical, political, or philosophical decision, drawing the company continually back to the great drama of Scripture, the creeds, and the history of the Church, and what they mean for investing today.

One of our five guiding principles at Denver Institute is to think theologically: “Embracing the call to be faithful stewards of the mysteries of Christ, we value programs that enable men and women to verbally articulate how Scripture, the historic church, and the gospel of grace influence their work and cultural engagement.” To do this, we need theologians to guide, illuminate, and advise. This is why having a resident theologian on our staff is a necessity, not a luxury. (Can’t convince your nonbelieving partners to hire a theologian? Fear not: the vast majority of theologians would happily take the title “Philosopher in Residence.”)

And on the bright side, compared to your typical MBA from Kellogg, theologians are relatively cheap. With thousands more PhDs in theology than there are professorships, there is certainly market supply.

Yet I’d say they’re worth their weight in gold. Some may balk at this comparison to theologians and gold: $1764 per ounce, assuming a 150-pound theologian, are they really worth $4,233,600?

Depending on what you’re investing in, they might just be…

***

Jeff Haanen is the Founder and CEO of the educational nonprofit Denver Institute for Faith & Work, CityGate, a national network of leaders working at the intersection of faith, work, justice and community renewal, and The Faith & Work Classroom, a free, online learning platform.

Giving can change us, but I’ve noticed it doesn’t change everybody equally.

Having closely observed hundreds of donors through my work as a fundraiser and nonprofit executive, I’ve tried to ask: what is the actual process of becoming like Christ through our giving? Is there a logic or pattern to the ways people change through their giving, especially Christians? Might giving actually move us backward in character growth, becoming cynical or even resentful of charities?

I’ve found there are generally three phases that God invites a giver to experience, represented by two questions about giving and finally a relinquishing of power.

“How much do I give?”

Spiritual Journey: The first step in the journey is discovering the other. Givers heed Jesus’ call to “love your neighbor as yourself” and use money as a tool to serve the needs of others. This is often an awakening to the needs of the world and the ways that money can be used to help meet spiritual, economic, and social needs.

This Phase is Characterized By: the movement from accumulation to generosity and from consumerism to philanthropy (or the love of anthropos, humans). Givers at this stage experience the exhilaration of giving and a new sense of making a community impact. The thrill of “doing good” for one’s community gives renewed interest in giving as a core aspect of a happy, fulfilled life.

Giving Habits: In this stage, the quantity of personal dollars given increases and is oftentimes sacrificial. They get used to giving larger amounts of money for the first time and are eager to see “impact metrics” or stories of changes from the various causes they support.

Key Scriptures: 2 Cor. 8 & 9; 1 John 3:16; Matthew 28:16-20. Givers in this stage are motivated by the “Macedonian call” for aid coming from the lost, the poor, or the various community needs they touch. Giving as impact and serving others is the core motivation.

“How much do I keep?”

Spiritual Journey: In this stage, the giver experiences a conversion. The conversation changes from “how much can I give?” to “how much should I keep?” The journey moves from one of outward impact to increasing dependence on God and a willingness to “embrace your limits as gifts” from God.

This Phase is Characterized By: the movement from generous giving and making an impact to contentment. The act of giving itself becomes an avenue of receiving God’s joy, and the giver becomes less interested in specifics of nonprofit or charity impact. Instead, new attention is paid to the spiritual lives and hearts of those you give to and those who are giving. Interior riches are increasingly experienced as gifts from God.

Giving Habits: Givers decide to set a ceiling on what they need to live on and give then give away anything they earn above that ceiling. As personal giving drastically increases, personal consumption now decreases as well. They experience humility and spiritual vibrancy, and they have a lessening awareness of sacrifice. Even as they see friends or peers spend money on houses, cars, trips or entertainment, they’re not bothered by what they’re missing out on, but instead find themselves feeling more whole, healthy, and joyful.

Key Scriptures: Philippians 4:11-13. Givers in this stage have “ learned the secret of being content in any situation.” They experience the joy of “enough” and the power of simplicity.

“I finally have everything I need.”

Spiritual Journey: The final stage of generous giving is the giving away not of money, but of power. The final temptation is relinquished and what lies behind money – which is power over others – is finally laid down. Power is gladly handed over to those with less knowledge or skill, both in work and in family, and God’s work through others becomes more tangible and real.

This Phase is Characterized By: the movement from contentment and sacrifice to self-forgetfulness. Money has finally lost its power as a blanket for security and all security is now found in the reality of God’s good provision and enduring Presence. Generosity spreads from giving money to also being generous with one’s time, attention, and prayers. They experience a genuine freedom from money. Simple pleasures – nature, smiles, smells, memories, words – regain their deep pleasure. For those who give away power, they find it easy to submit to the decisions and leadership of others.

Giving Habits: Givers in this phase give away the means of power, not just money itself. They give away equity in their businesses or decision making-power in their family foundations, including say-so over where the money goes or how it’s spent. In this phase, wealth is given at both personal and business levels. Yet for many, they experience this phase having very little in terms of worldly wealth. They’re released of the need for impact and instead experience a deepening experience of the delight of God. They become indifferent to wealth and cling instead to Christ himself as the final, lasting treasure.

Key Scriptures: Philippians 2:7; Matthew 13:45-46; Philippians 3:7-8; Romans 8:34; Matthew 19:21. This final phase looks like the kenosis, the self-emptying of God through incarnation and ultimately cross of Christ. The call to “sell everything you have and give to the poor” is seen not as a loss, but the great deal that it truly is: the gaining of a treasure of far more value. They “consider all things loss compared to the surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus” and enter into deep freedom from anxiety, security and control. Givers finally say, “The Lord is my Shepherd. I have everything I need.”